Making games easier to run at Ubisoft

How I helped turn a complex, API-first platform into something teams could understand, trust, and operate.

Snapshot

It’s Saturday night. Friends are online, snacks are ready, and you’re about to jump into a match. Instead, you’re stuck watching a loading spinner. To players, the game feels broken. A few minutes later, they move on.

Running games at scale

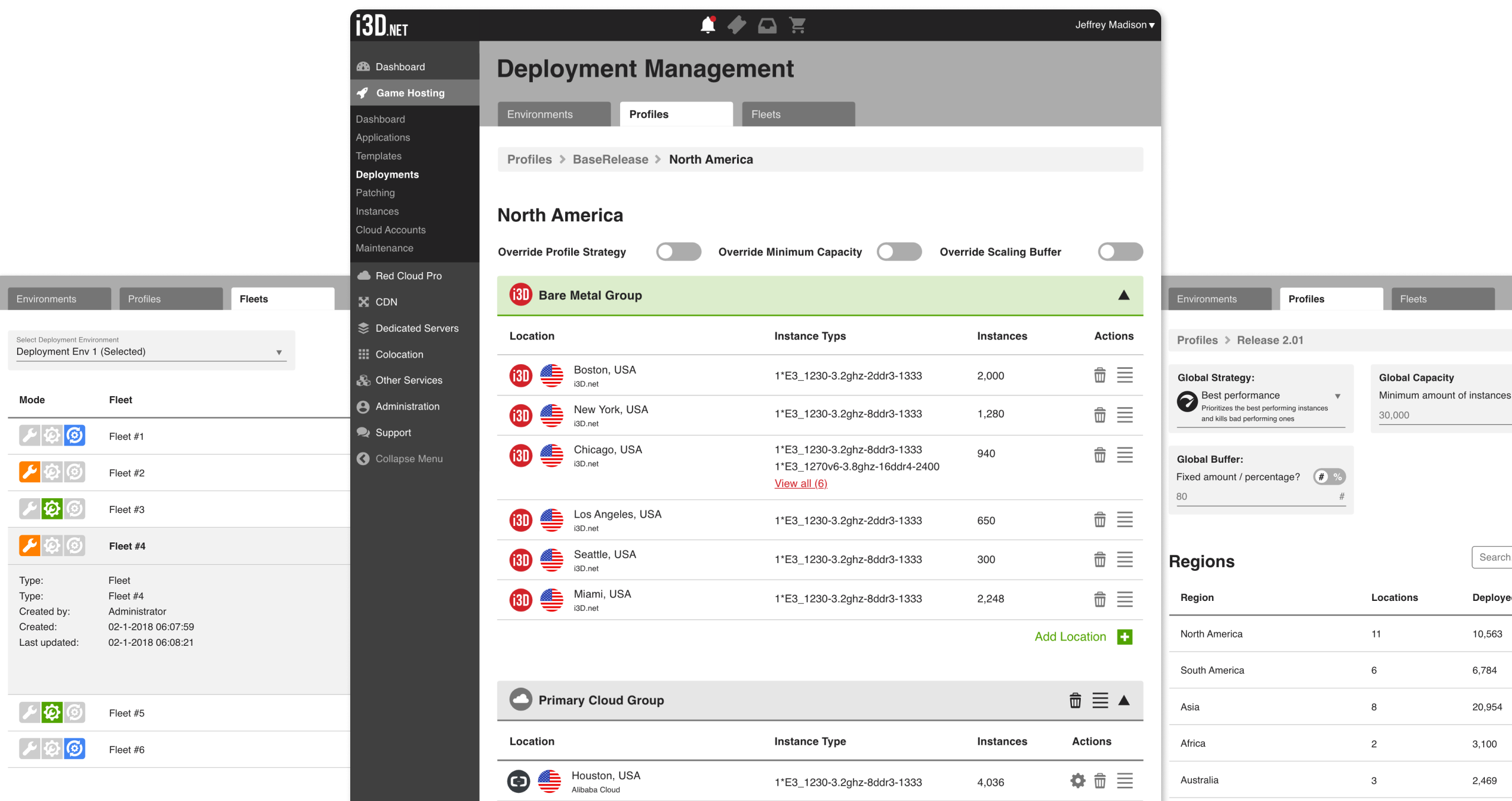

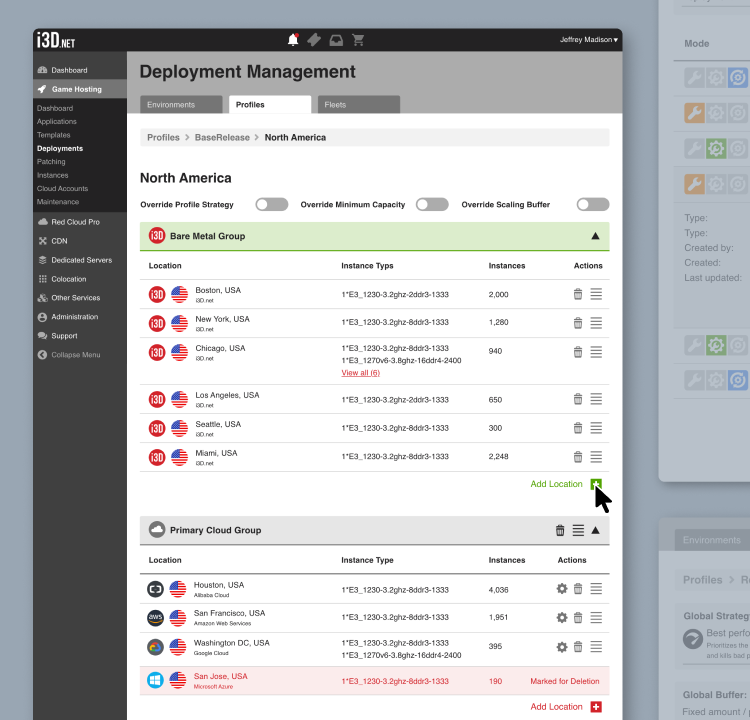

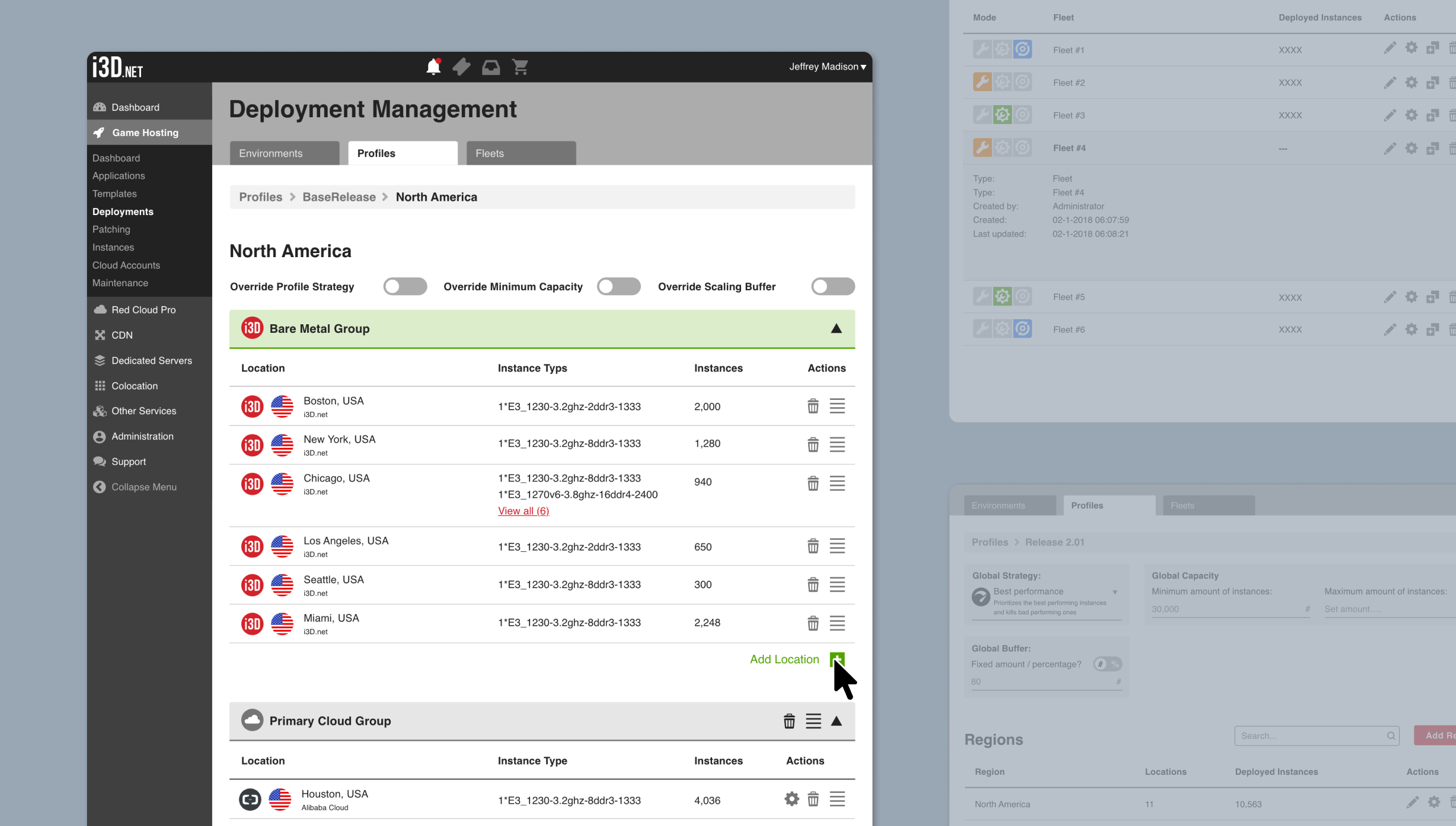

At Ubisoft, i3D provides the infrastructure that keeps online games running. It scales servers across bare metal, flex resources, and cloud as player demand rises and falls across regions. The platform is built to handle millions of players and sudden traffic spikes.

That power came with real complexity. Configuration was spread across documentation, APIs, and dashboards, and it wasn’t always clear how decisions would play out once systems went live. During testing, a small configuration mistake caused far more resources to spin up than intended. Nothing broke, but the cost made the risk obvious.

My focus

As lead product designer on i3D, I focused on how configuration decisions affected live Ubisoft games like The Division, Rainbow Six Siege, and Skull and Bones. The challenge wasn’t scaling infrastructure itself, but helping teams understand how their choices would impact player experience, stability, and cost once traffic hit, and giving them confidence to operate safely while games were live.

The Core Problem

An internal Ubisoft team working on Skull and Bones wanted to rely on the i3D platform for an upcoming release. That set clear stakes early on: this wasn’t a theoretical system, it needed to hold up under real player load and a fixed launch window.

The platform started as an API that could handle complex scaling scenarios across regions and infrastructure types. The system exposed powerful capabilities, but operating it meant stitching together APIs, documentation, internal tools, and monitoring dashboards. A frontend was always part of the long-term plan, but it wasn’t the immediate priority.

As teams started using the system in practice, friction showed up quickly. The challenge wasn’t a lack of features. It was that configuration lived across multiple layers, and it was hard to keep a clear mental model of how those layers interacted. Small changes could have wide effects, and it wasn’t always obvious how inputs translated into runtime behavior.

Powerful, but hard to predict

We ran into this ourselves during testing. We made a configuration mistake and ended up spinning up far more resources than intended. Nothing broke, but the bill hurt enough to get our attention. If this could happen during controlled tests, the risk during a live launch with real players was obvious.

The problem wasn’t access to the system. It was not being able to confidently predict what a configuration would actually do once things were running. Despite the system’s flexibility, it often felt like a black box at the moments when teams needed clarity most.

How We Worked

When I joined, most of the system already existed in code and documentation, but its behavior was difficult to reason about. Given how costly mistakes could be, the work started with building shared understanding, not screens. That meant getting close to the system before deciding what it should look like.

Building a shared mental model

I partnered closely with a product owner who had previously engineered the system. We met biweekly to walk through scenarios, edge cases, and assumptions, often comparing what we expected to happen with what actually happened. These sessions surfaced hidden coupling between configuration layers and areas where runtime behavior was unclear.

I also embedded myself with the engineering team and regularly joined their meetings. Staying close to the work gave me space to ask naïve questions, challenge assumptions, and surface gaps early, before they hardened into product behavior.

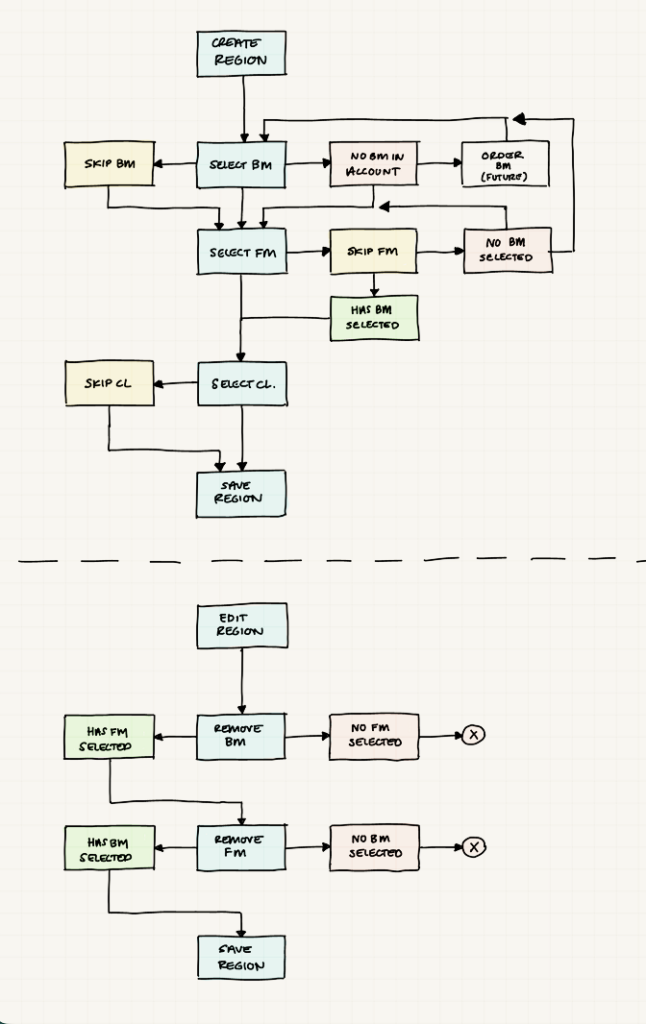

Unpacking the system

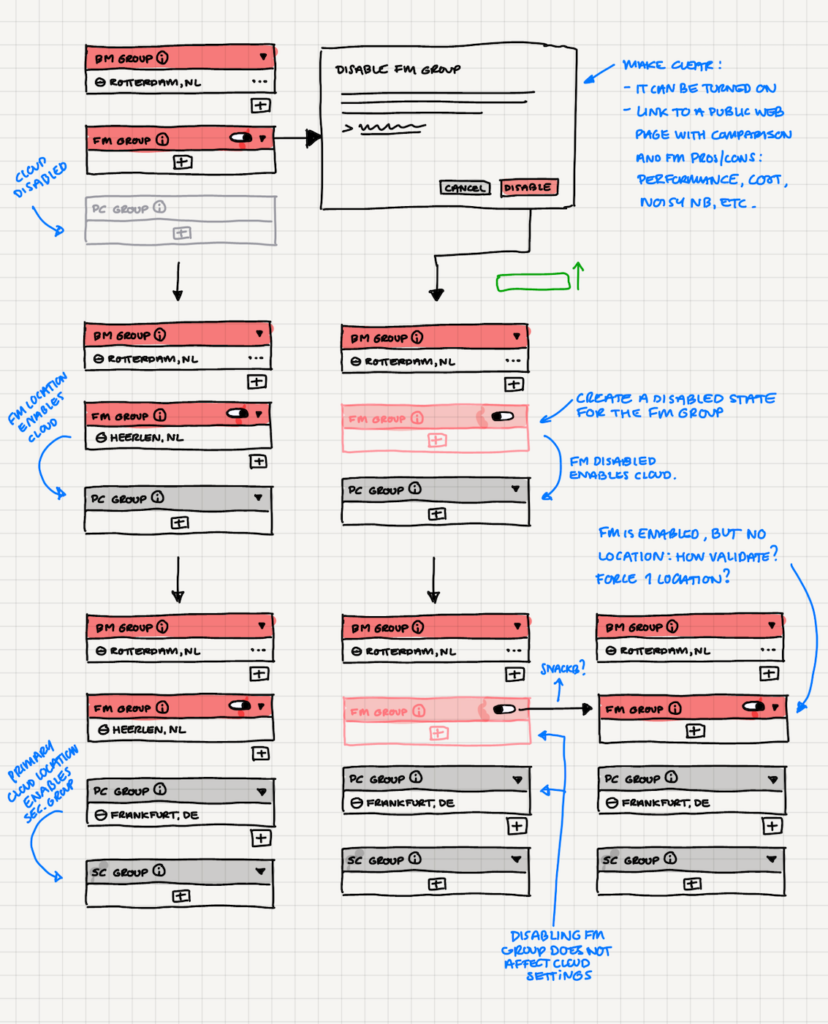

I externalized my understanding through diagrams and rough wireframes. These were not about polish. They were tools to reason about dependencies, explore valid and invalid configuration paths, and understand how choices cascaded into runtime behavior. Making the system visible made it possible to critique, align, and iterate together.

Testing played a constant role. Load and performance tests validated the backend, while I focused on whether the experience supported confident decision-making, especially under pressure. LiveOps teams were closely involved, providing fast feedback grounded in real operational scenarios.

Making the system easier to operate

The problem was not knowing what would happen once a configuration went live.

Before this work, teams configured the system through APIs and documentation and then waited to see how it behaved. You could set almost anything, but understanding the outcome meant piecing things together yourself. Even small changes required double-checking, and mistakes were easy to make.

Visible outcomes

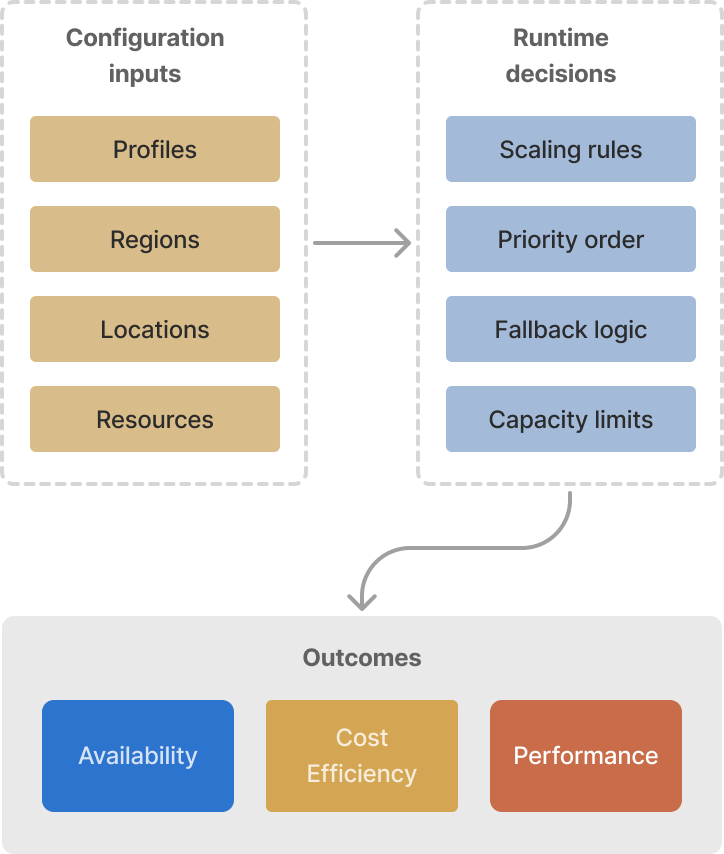

What we changed was how configuration was expressed and understood. Instead of working with loose parameters, configuration was structured around how the system actually operated: which resources would be used first, what happened when capacity ran out, and where traffic would go next. Priority and fallback were no longer implicit. They were part of the setup.

Configuration and monitoring were brought closer together. Teams could see what was configured, where it applied, and how it behaved while tests were running. That made it easier to spot risky setups early, validate expectations, and adjust before issues showed up in production.

The system didn’t become simpler. But it became clearer. Teams could set things up with more confidence, knowing what they were asking the system to do and what it would do in return.

Once the system’s behavior was visible, a set of design constraints became obvious. The following decisions came directly out of those constraints.

Key Decisions

Decision 1

We didn’t design for everyone

This is a highly technical product. Even after improving usability, documentation and technical knowledge remained part of using it, by design.

We considered adding onboarding and guidance to lower the barrier for less experienced teams. Given time constraints and the product’s maturity, we chose not to. That effort would have pulled focus away from the teams we were building for.

Instead, we prioritized experienced developers, LiveOps, and internal teams who needed predictability over hand-holding. The goal wasn’t to remove complexity, but to make the system’s behavior clear and dependable.

This trade-off let us ship faster, reduce misconfiguration risk, and treat broader onboarding as a future investment rather than a blocker.

| Criteria | Design for everyone | Design for clarity |

|---|---|---|

| Solves core problem | ❌ No | ✅ Yes |

| Risk of misconfiguration | ⚠️ High | ✅ Lower |

| Speed to MVP | ❌ Slow | ✅ Faster |

| UX complexity | ❌ High | ✅ Controlled |

| Outcome | ❌ Rejected | ✅ Chosen |

Decision 2

Strong defaults over enforcement

The preferred setup was clear: bare metal first, then flex metal, and finally cloud for peak demand or low-capacity regions. Bare metal delivered the best performance and cost profile. Flex metal came close, but with higher commitment costs. Cloud acted as the safety net.

Originally, flex metal was mandatory before falling back to cloud. In practice, this was too restrictive. Some publishers already had their own cloud accounts, and forcing them through flex metal once bare metal was exhausted did not always make sense.

I pushed to make flex metal optional. The assumption was that most teams would still follow the defaults, but allowing flexibility preserved trust and respected different studio setups. The goal was not to enforce a single “correct” path, but to guide behavior through strong defaults.

Impact and Reflection

As the platform saw heavier use, configuring and operating deployments became noticeably calmer. Teams moved faster during testing, made fewer costly mistakes, and spent less time second-guessing configuration changes. The system became easier to onboard onto, not because it was simpler, but because its behavior was easier to anticipate.

That clarity shifted conversations beyond engineering. Instead of explaining how the platform worked, teams could focus on whether it was ready for launch. This helped secure early hosting regions for major titles, including Skull and Bones, and supported launches for games like Rocket League and The Division 2. The impact was not just internal confidence, but real production usage under pressure.

Looking back

Much of the platform was built from scratch under real delivery pressure. In hindsight, adopting an existing design system earlier would have reduced some long-term overhead. At the time, supporting live launches and keeping teams moving mattered more.

What I would not change is the focus on making system behavior explicit before adding polish. That foundation made everything that followed possible.

Final Takeaway

This project reinforced that understanding complex systems does not come from reading documentation alone. It comes from getting close to the people building and running them, asking naïve questions, and unpacking assumptions together.

The biggest progress did not happen in isolation. It came from working alongside engineers, product, and LiveOps, turning implicit knowledge into something shared, discussable, and actionable.

That collaboration is what ultimately made the system operable. Not by making it simpler, but by making its behavior clear enough to trust.

If you want to discuss this work, feel free to reach out.