Spotiverse: Turning my Spotify library into a visual map with AI

How a personal frustration with music discovery led me to rethink browsing a large Spotify library, exploring visual maps as an alternative to endless lists. Mapping my library made discovery feel intentional again, instead of endless scrolling.

A note before diving in: Spotiverse is a personal project and an ongoing exploration. This page covers the motivation, early prototypes, and the lessons learned while using AI tools to turn a wild idea into something tangible.

Music, formats, and scale

Music has been a constant in my life for as long as I can remember, and in many ways my relationship with it has evolved alongside the formats used to store and play it.

It started with a small collection of vinyl records at home, shaped mostly by what was playing around me rather than by deliberate choice. Dire Straits, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who. As a kid, music was something you absorbed passively. It was always there, but it wasn’t yet something you managed.

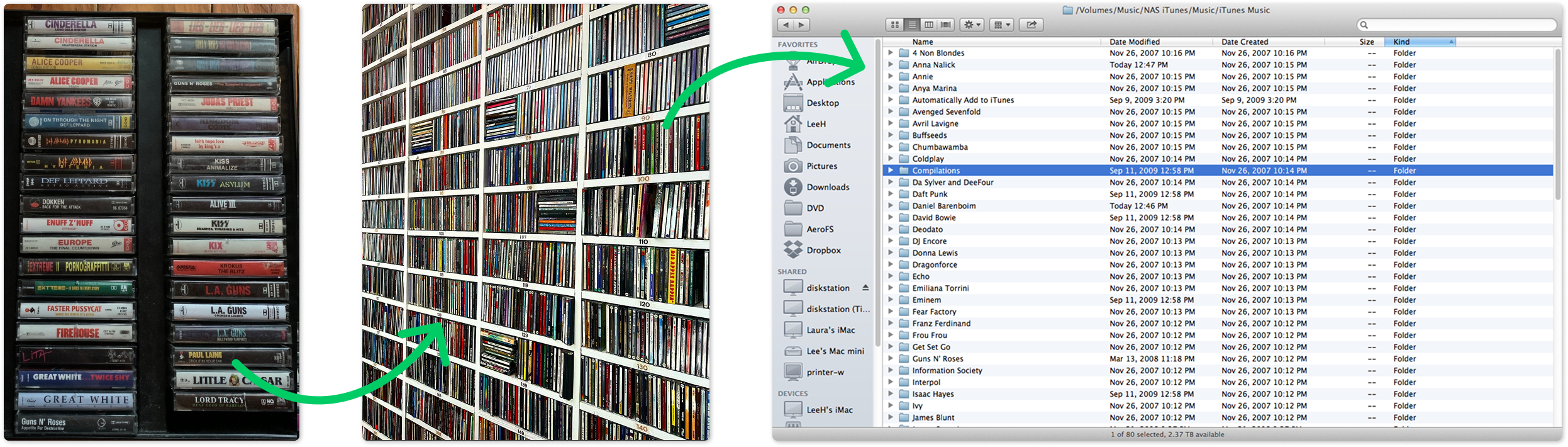

That changed during my teenage years, when cassette tapes entered the picture. Recording songs from the radio and making my own mixtapes was the first time music started to feel personal. I wasn’t just listening anymore, I was curating. When CDs became mainstream, that sense of ownership intensified. My collection grew quickly, eventually filling boxes that now sit in the attic.

In the early 2000s, iTunes and mp3s arrived, and with them a new kind of freedom. Combined with how easy it was at the time to get music from the internet, my library exploded. Hundreds of artists turned into thousands. Albums, playlists, folders. I started building structures just to keep things manageable, grouping music by genre and creating hierarchies to impose some sense of order.

That system held for a while, until it didn’t. My hard drive reached its limits, iTunes took ages to start up, or would occasionally crash, and something that was supposed to be enjoyable slowly became frustrating. Finding music took effort. Listening felt interrupted.

To cope with that, I started relying more on my mp3 player, and later my phone. I would sync or copy a carefully selected subset of music from my library and listen to that instead. Every now and then, I’d wipe it clean and start fresh with a new selection. In theory, this was a way to stay intentional. In practice, it became another form of friction.

As my library kept growing exponentially, that curation process became time-consuming and increasingly annoying. Faced with the effort of reselecting music, I often defaulted to copying over familiar albums and artists. Over time, I noticed I was listening to the same things more and more, not because I wanted to, but because they were easier to reach.

Spotify, and a familiar problem

When Spotify arrived, it felt like the end of that struggle. Storage limits disappeared. Performance was no longer an issue. Suddenly, pretty much all music in the world was available instantly. From an access and scale perspective, the problem was solved. But over time, a familiar pattern resurfaced…

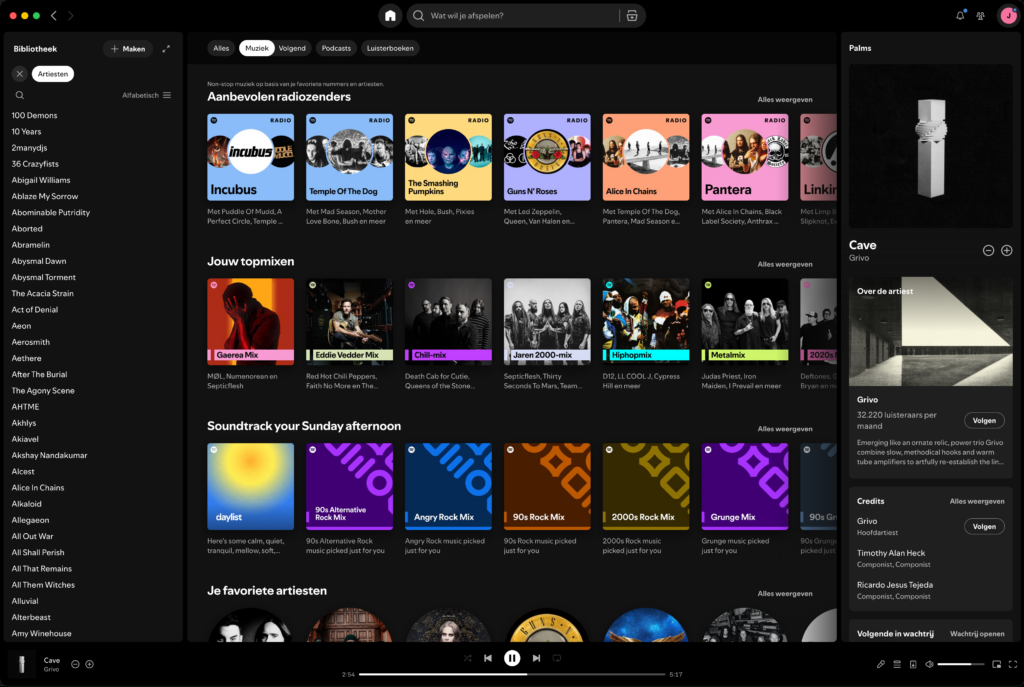

I’m a heavy Spotify user. On average, I listen to 3 hours of music a day. I follow over 500 artists, which turns into a long sequence of names without context. No genres, no relationships, no sense of proximity. When I want to listen to music, I often know the direction I’m in the mood for, but not the exact artist or album. Choosing what to play starts to feel oddly familiar, in the same way it once did with mp3s.

Most of the time, I end up scrolling through the same list and playing something familiar. Sometimes I give the scroll wheel a hard spin, close my eyes, click play, and see what happens. That can be fun, but it’s unreliable. When music needs to align with a mood or a moment, randomness is a risky strategy.

Spotify offers tools like Artist Radio, and they help to some extent. But radios for related artists often converge on the same tracks, and after a while they start to feel narrow and repetitive. What I was missing wasn’t access, or even discovery in the traditional sense. It was a way to explore intentionally, without falling into the same patterns every time.

Reimagining browsing using AI

At some point, the question shifted from what I should listen to, to how I was browsing in the first place.

I’m drawn to visuals, and especially to infographics. When I started experimenting with ChatGPT, it felt like a low-friction way to explore an idea that had been taking shape for a while. What if browsing music could feel more like exploring an interactive infographic than scrolling through lists?

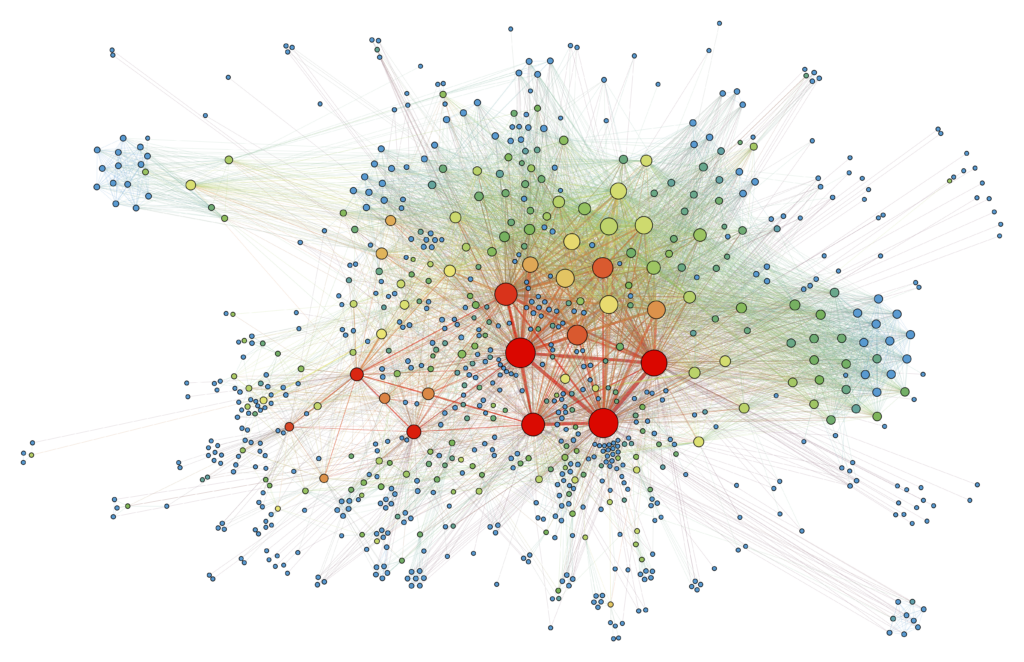

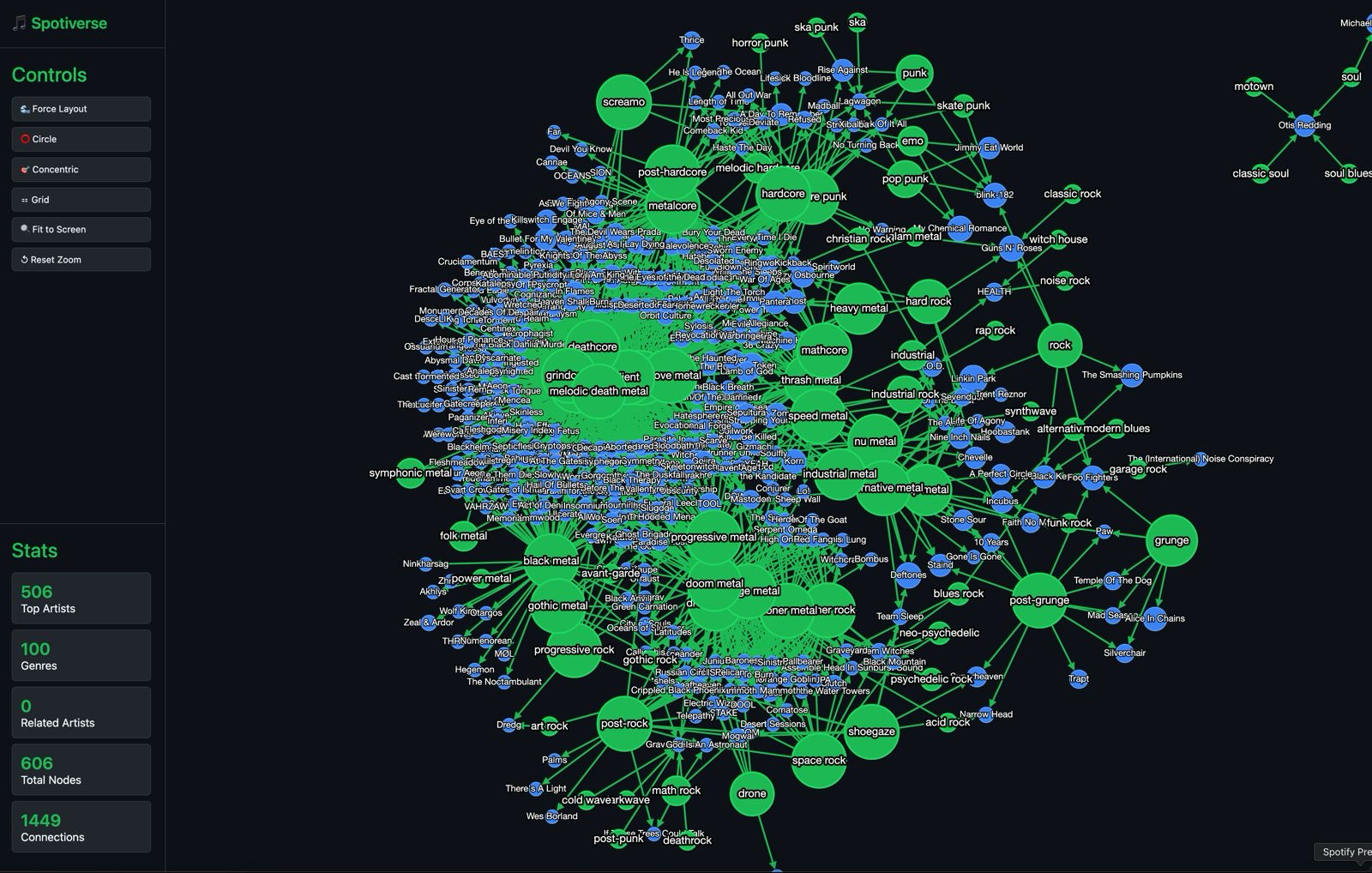

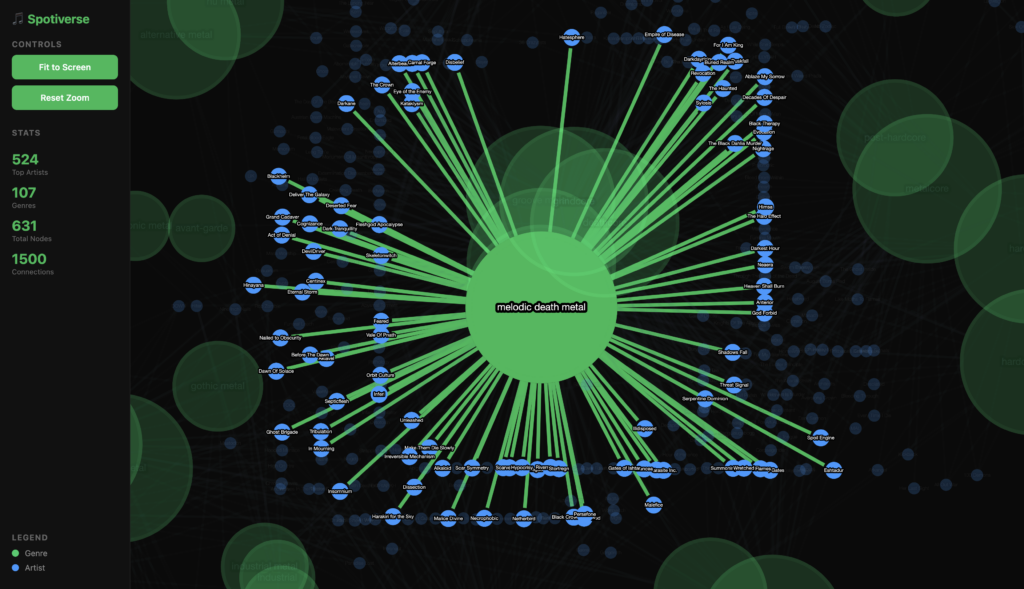

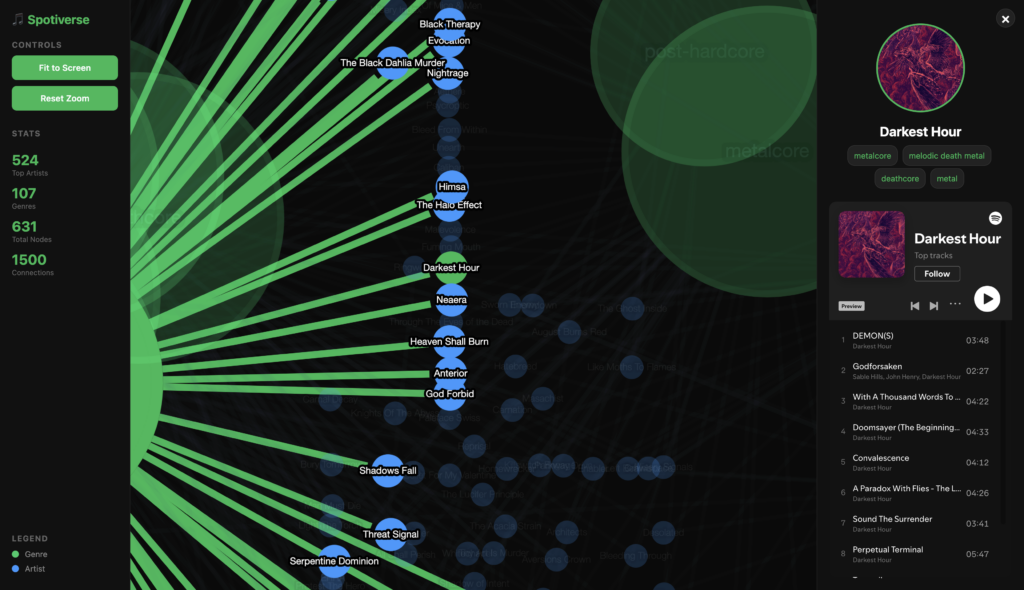

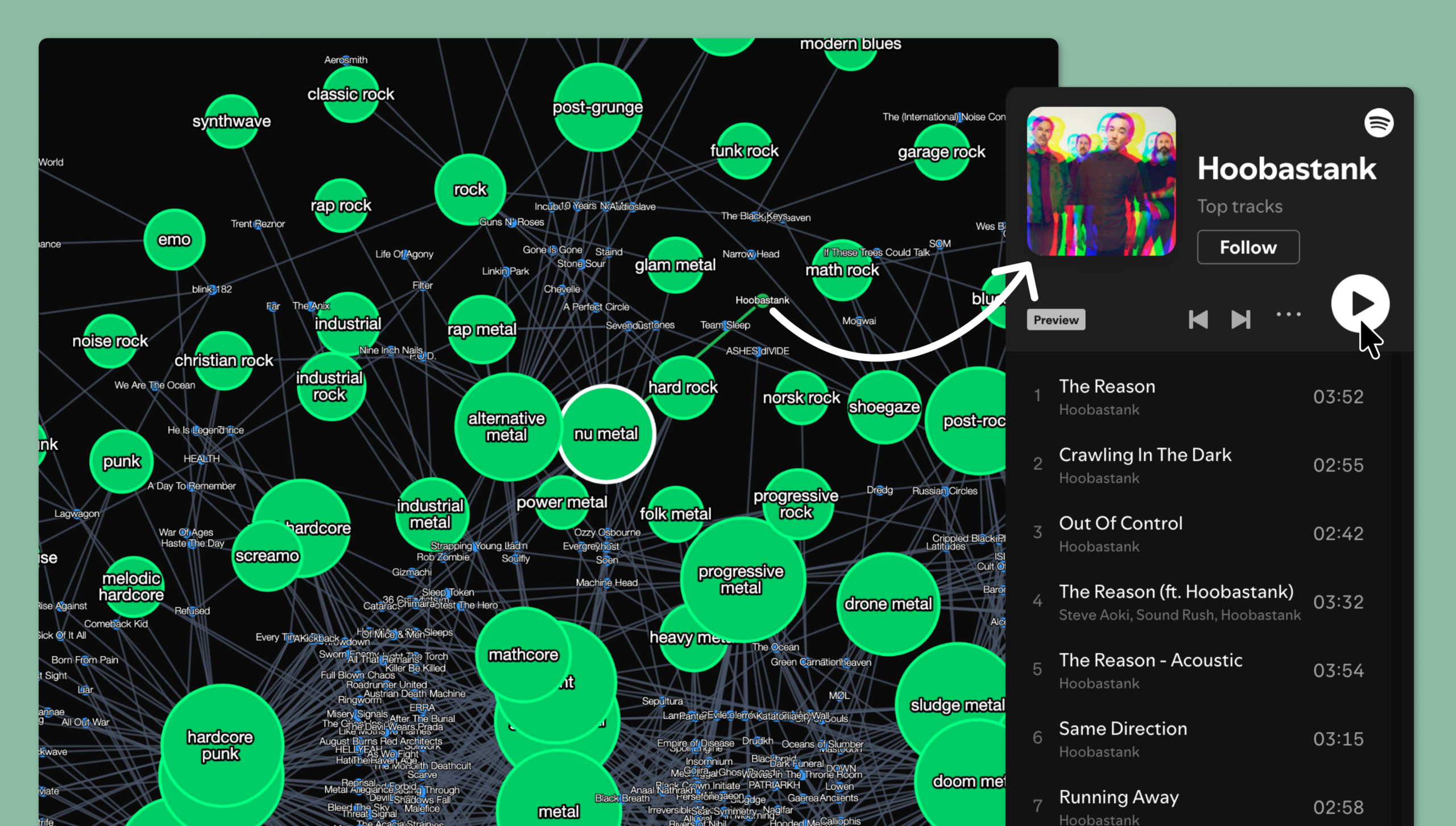

Instead of thinking in terms of screens or flows, I focused on representation. I imagined my Spotify library as something spatial rather than linear. Artists and genres as clusters. Relationships made visible instead of implied. Something closer to a heatmap or a relational diagram than a traditional list.

At that stage, this was still just an idea.

From experiment to prototype

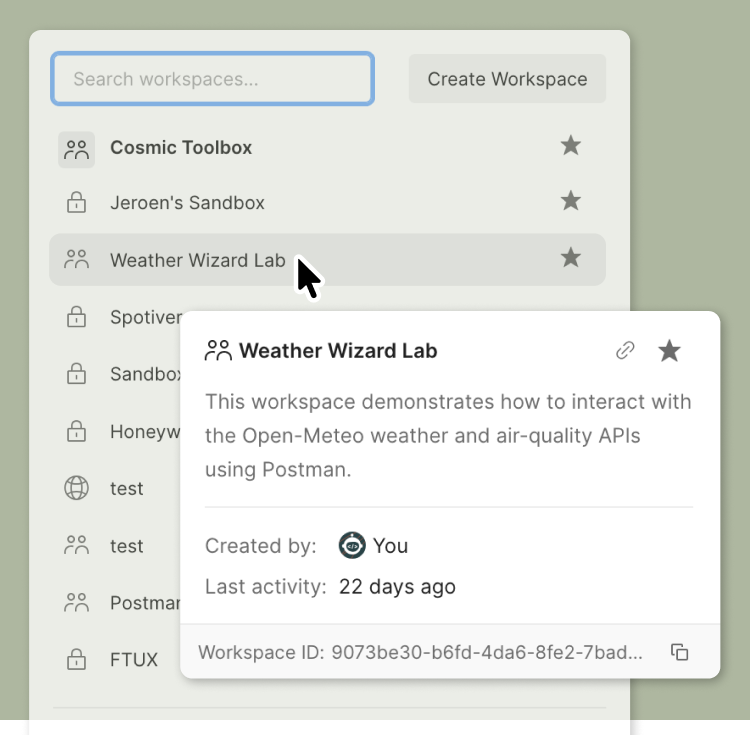

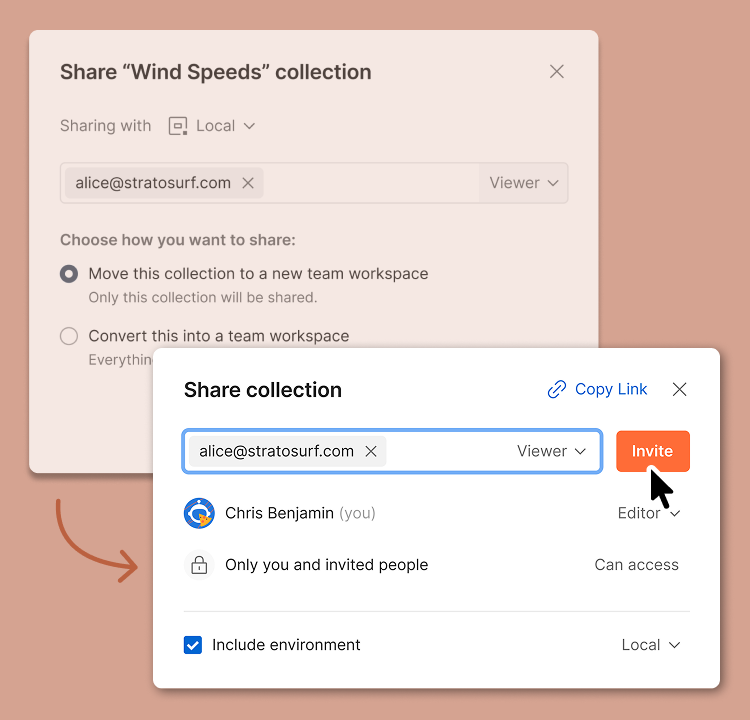

To explore whether that idea could actually work, I moved from exploration to implementation. I used ChatGPT and Cursor side by side to translate the concept into something tangible, focusing on getting a basic prototype running rather than solving everything upfront.

This was also the point where the project stopped being purely conceptual. I connected to the Spotify API, handled authentication, and started working with my own listening data. That step alone came with its own challenges, but once it worked, it grounded the project in reality. Seeing real artists and genres appear in a visual structure immediately raised new questions about scale, structure, and interaction.

The prototype was rough and fragile. The UX wasn’t great, but it worked well enough to test the core idea. AI sped up exploration, but the framing, constraints, and decisions were mine.

The first signal it worked

The first time I saw the visualization come together, even in a very early state, it felt different from anything Spotify offered.

I could zoom into an area that matched my mood for the day and focus there. Within that space, I’d find artists I listened to often, but also artists I vaguely remembered and hadn’t actively looked for in years. Rediscovery stopped being accidental and started to feel intentional.

That moment was enough to validate the direction. The tool didn’t need to be polished to prove that a different way of browsing could already reduce some of the original friction.

When things started to strain

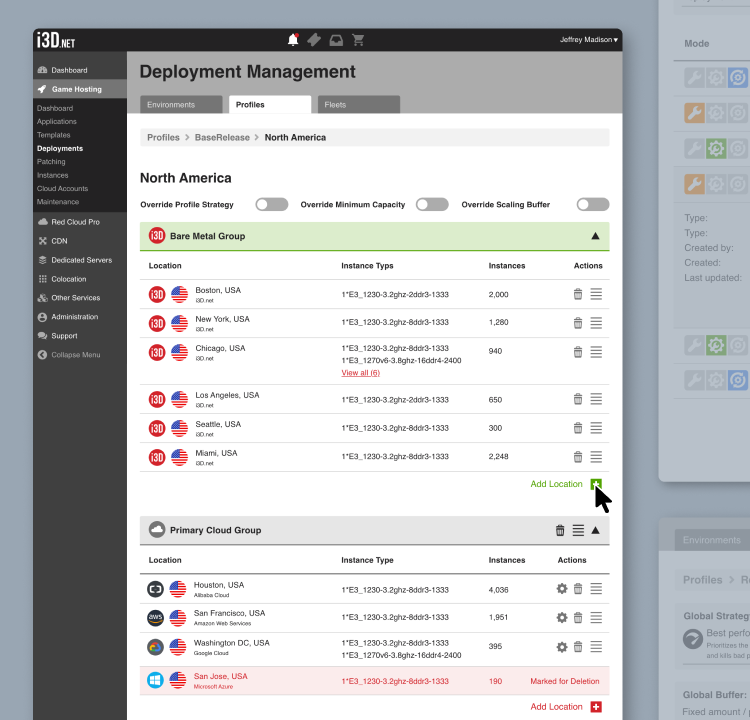

Things became more complicated when I tried to take the prototype beyond my local setup. I wanted to make it accessible through a URL, so I attempted to deploy it on an online hosting service.

While I eventually got it working again with the help of AI, something had changed. Many of the fixes solved immediate problems, but they also made it harder for me to reason about the system as a whole.

The prototype worked, but my understanding lagged behind. That tension mattered more to me than the deployment issues themselves.

Pausing with intent

The passion for the project never disappeared. What changed was how I looked at the work.

Building Spotiverse taught me something I now recognize more clearly in my day-to-day work. When working with AI, it’s easy to move fast and make a lot of progress, but it’s just as easy to lose track of what’s actually happening under the hood. You can end up with something that works, without fully understanding why.

Over time, I’ve learned to spot those moments earlier. When things start to feel fuzzy, I’ve learned to pause, step back, and decide whether it makes sense to continue, undo changes, or rethink the approach. I’ve also become more deliberate in how I use AI, setting clearer boundaries and being more explicit about what it should and shouldn’t do.

The Spotiverse prototype did what it needed to do. It helped validate the idea and exposed the limits of my understanding, the limits of AI assistance, and the constraints of Spotify’s ecosystem. Even though the prototype works today, the process itself changed how I think about building things like this.

This project reinforced my belief that interfaces for abundance need structure, not more options. Mapping complexity beats hiding it.

If you want to discuss this work, feel free to reach out.